Water Smart Cities Project

Article

Article

‘The events of July 2021 are a reminder that flooding has always been, and still is, a risk for people living along the banks of our rivers.The city of Liège was hard hit in the neighbourhoods around the confluence of the Ourthe. But the situation could have been much worse had it not been for the ‘demerging’ infrastructure. In the following article, CEBEDEAU gives the floor to Jean-Pierre Silan, Advisor to the General Management of AIDE, in charge of demerging and purifying the municipalities of the province of Liège.

Floods are natural phenomena that have always shaped the landscape of our rivers and affected the lives of people living along their banks.

The floods that hit Wallonia this summer were considered by the Prime Minister to be ‘without precedent in our country’.

These catastrophic floods are neither the first nor the last. In the Liège region, they echo those that ravaged the region in the winter of 1925-1926.

What were these floods and what measures were put in place at the time? How did the works withstand the exceptional events of that summer?

The 1925-1926 floods in Liège owed their extraordinary violence to the very heavy snowfalls that hit the country in late November and early December 1925.

From 19 December 1925, extremely heavy rainfall, combined with melting snow, caused exceptional flooding of the Meuse and its tributaries.

In Liège, the flooding of the Meuse reached its peak on New Year's Eve. Liège city centre was flooded as the river overflowed its banks. However, the situation was much more serious upstream of Liège, in the urban and industrial areas of Flémalle, Ivoz, Jemeppe, Tilleur, Seraing and Ougrée, where underground coal mining had caused major subsidence of the surface land, up to 6 metres, making these areas increasingly vulnerable to flooding.

The damage is considerable. Nearly 6,000 houses have had their ground floors flooded. More than a thousand were flooded up to the first floor. All the major factories and collieries on the plain were paralysed for the many months it took to restore their facilities, leading to prolonged unemployment for most of the working population. Trade was also hit hard.

The consequences of the floods of 1925-1926 were such that they risked causing the exodus of large-scale industry, the total ruin of commerce and misery for more than 150,000 people. The public authorities had to react.

Despite this, coal mining continued unabated. It did not stop until the end of the 1970s, for economic reasons.

After the floods of 1926, a number of political and technical measures were taken.

The Belgian government very quickly built powerful dykes to contain the highest floods and began major rectification work on the river (removal of islands and dams, dredging, etc.) to regulate the river's flow.

This work proved to be effective, as during the floods of 1995, for example, which were on a similar scale to those of 1926, the Meuse remained in its bed, at least as it passed through the Liège region.

However, containing the river between dykes and lowering the hydraulic axis of the maximum flood is not enough to save the region.

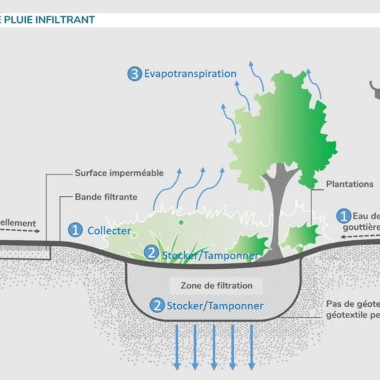

Indeed, as a result of the dyking, the wastewater and rainwater falling on the plain and down the surrounding hills can no longer flow normally towards the Meuse, as all hydraulic communication between the river and the plain is impossible.

In addition to direct protection against flooding from the river, it was therefore absolutely essential to put in place a system to keep dry the collapsed areas where the water could no longer reach the Meuse naturally at all times. The system devised at the time was called ‘demerging’.

Designed by Mr Hector BIEFNOT (1869 - 1936), the demerging project was based on an assessment of potential mine subsidence, maximum flood levels, reference rainfall profiles and the phasing of dyke construction.

Two main principles have been put in place:

- Collection of water from higher ground and its transfer to watertight gravity outlets discharging into the Meuse ;

- the collection of water produced on the alluvial plain (wastewater, springs, mine drainage, runoff, water seeping into cellars) and its discharge into the Meuse, either permanently or during flood periods, using pumping stations.

The gradual implementation of this system is in the hands of the local authorities, with significant financial support from the government.

To this end, in 1928 the main municipalities upstream of Liège affected by flooding set up an intercommunal association (A.I.D., which has since become AIDE) to build, maintain and operate flood control facilities. The Province of Liège also joined the intercommunal association. Other towns and municipalities concerned joined later. AIDE has therefore been designing, building and operating dewatering facilities for almost a century, to the satisfaction of the authorities and the public.

Demining work continues to this day. In the meantime, drainage has become a regional issue, coordinated and financed by the SPGE.

Liège's flood control system ensures that the 1,562 ha of urban areas vulnerable to flooding are protected at all times, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, even when the Meuse is at low water. Without it, large parts of the alluvial plain would be permanently flooded. However, it is only during spectacular floods that its importance is fully appreciated by the authorities and local residents.

During this summer's floods, demarcation protected local residents and buildings that would otherwise have been devastated.

Unfortunately, there was one notable exception: the Angleur district was flooded by the rising Ourthe, which reached levels never before measured.

The importance of direct protection should be borne in mind here: if the dykes are overtopped and the alluvial plain is flooded, the drainage system works like a duck, pumping the water into the river, which in turn feeds the pumping stations. In this scenario, the demersal system is inoperable and pumping has to be stopped.

Pumping stations no. 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13, which provide water for Angleur, were submerged by the waters of the Ourthe. They suffered serious damage that prevented them from being restarted immediately. Thanks to AIDE's operations teams, these five stations were quickly back in service, with the system fully restored less than a week after the events, sometimes using temporary solutions.

Elsewhere, dismantling ensured the protection of :

- 12,935 residential buildings housing more than 30,000 people

- 190 business premises

- 51 schools

- a hundred or so public buildings (administrations, hospitals, nursing homes, crèches, post offices, police stations, fire stations, cultural establishments, sports halls, water towers, electricity stations, cemeteries, places of worship, etc.).

- 144 km of roads, including major access routes along the Meuse river, used by the population and the emergency services.

Insofar as a comparison can be made with the damage caused in 1926, the cost of the damage spared by dismantling during the recent events would be at least €900 million. This does not, of course, include the social trauma or the disruption to economic activity, which are indirect consequences of the flooding.

The cost of de-risking infrastructure and keeping it in good working order is therefore largely recouped by the occurrence of a flood of the secular type.

5. What lessons can be learned?

The lessons to be learned from these extreme events, which put a greater strain on infrastructure, include

- the vital importance of direct protection against flooding of the Meuse and, in this case, the Ourthe, managed by the Walloon Region's navigable watercourse services

- the rare occurrence of a secular flood in summer, which could have been accompanied by stormy episodes (as was the case in Germany);

- The importance of having a dual power supply for all pumping stations, so as to guarantee the availability of at least one sufficient source of energy;

- The need to maintain access to facilities in the event of flooding.

It is essential for AIDE to check the suitability and resilience of its works in the face of climate change and to undertake, with its partners and the SPGE, major adaptation, rehabilitation, renovation and modernisation work to enable demining to fulfil its missions effectively and sustainably.

The regional authorities should ensure the effectiveness of direct flood protection for the Meuse, Ourthe and Vesdre rivers as they flow through the Liège conurbation, taking into account the effects of climate change. Lastly, funding for dismantling must be guaranteed for the major investments to be made over the next few years.

This is the only way that AIDE will be able to continue to carry out its mission effectively and with peace of mind.

www.aide.be

par Jean-Pierre SIlan

Article

Article

Event